How I Learned to Cook in Just Fifty-Five Short Years

A master chef shares her culinary secrets

I’ve heard the famous quote by Confucius a hundred times, "I hear and I forget; I see and I remember; I do and I understand” but it just now dawned on me what he was referring to. He was talking about learning to cook! I know it’s true because I’ve had the exact same experience myself.

For me the journey to culinary enlightenment began a long time ago in a Ford Galaxy far, far away. The year was 1964 and I was ten years old on vacation with my family, which included my parents, my two sisters and on this particular occasion, my grandmother and her sister. Now I loved my grandmother deeply, but I’ll be perfectly honest here. Until you’ve been trapped in a crowded car all the way from Midland, Texas to Anaheim, California and back with someone reading recipes for King Ranch Chicken aloud from McCall’s Magazine, you can’t begin to know the meaning of the word agony. I must have listened to a million recipes, but oddly enough, the only thing I can recall about any of them is that they all seemed to have one common ingredient – Cream of Mushroom Soup. In other words, I heard but I forgot.

My next experience involves the middle precept of the quote, namely seeing and remembering. Long before there was Paula Deen or Rachel Ray or the Barefoot Contessa there was my mom. She was a fabulous cook, no two ways about it. But the thing is, she was a bit of a lone wolf in the kitchen. Oh sure, when it came to mundane chores like setting the table, unloading the dishwasher, and washing the pots and pans, we were pressed into service, but by and large the task of preparing the meal was something she preferred to do on her own. What’s more, she didn’t use recipes very much. Her approach was to "wing it”, tossing a little bit of this and not too much of that into the skillet until it looked about right, which sort of explains the way she handed down the skill of cooking to her daughters.

My next experience involves the middle precept of the quote, namely seeing and remembering. Long before there was Paula Deen or Rachel Ray or the Barefoot Contessa there was my mom. She was a fabulous cook, no two ways about it. But the thing is, she was a bit of a lone wolf in the kitchen. Oh sure, when it came to mundane chores like setting the table, unloading the dishwasher, and washing the pots and pans, we were pressed into service, but by and large the task of preparing the meal was something she preferred to do on her own. What’s more, she didn’t use recipes very much. Her approach was to "wing it”, tossing a little bit of this and not too much of that into the skillet until it looked about right, which sort of explains the way she handed down the skill of cooking to her daughters.

When each of us three girls got married, Mom diligently typed up on small index cards the way to prepare our favorite Jolly family dishes. To read one of Mom’s cards was like having a cup of coffee with her while she talked casually about how to prepare a particular meal. "A pot of vegetable soup is a good thing to fix on a cold winter night” it would say. And each card was worded in such a way that it was like we could literally hear her voice. "You don’t want to add the milk to your gravy until you’ve stirred away all the lumps of flour.”

It was apparent from her directions (or lack of them) that Mom expected us to interpret amounts that were no more specific than "a pretty good sized piece of round steak”, "just enough flour to make a nice batter”, "a little bit of Worcestershire” or "some of the juice.” Obviously she just assumed we’d know what to do when we read, "You’ll probably need to thicken the sauce a little bit toward the end.” Thicken it how? And with what?

I don’t know if she realized it or not, but these rather vague, unorthodox methods of instruction were a lot more familiar to us than if Mom had given us precise, step-by-step recipes. We first had to figure out just exactly what "let the beans cook down for a little while” meant, and then we had to get there pretty much on our own. But oddly enough, we managed. How? It’s simple, really. We’d been watching her all those years. I can’t count the number of times I observed my mom as she carefully took spoonfuls of hot thickened cornmeal out of the pan and deftly rolled them into tiny football shapes and placed them on a sheet of waxed paper to cool before dropping them into oil and frying them golden brown. So years later, when she typed out her note card for "Corn Pones” I knew exactly what she was talking about because I had seen her do it. To put it another way, I saw and I remembered.

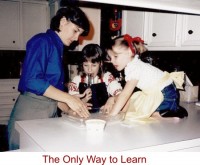

As my own kids came along I really had to work at letting them help in the kitchen because frankly, as I suspect my mother knew all along, it was a whole lot faster and neater to whip up a batch of chicken-fried steak myself than to turn my offspring loose with raw meat, buttermilk, flour and hot grease! But for the most part I tried to involve them in the process whenever I could because I wanted them to learn how to cook themselves. (No, I don’t mean cook themselves, silly; I mean cook for themselves.) Like everything else, there is no better teacher than experience. You can watch someone crack a thousand eggs, but until you try it yourself, you won’t be able to feel how much pressure it takes to break the shell without damaging the yolk. Breaking an egg takes practice. So does stirring and chopping and peeling and measuring and pouring and kneading.

As my own kids came along I really had to work at letting them help in the kitchen because frankly, as I suspect my mother knew all along, it was a whole lot faster and neater to whip up a batch of chicken-fried steak myself than to turn my offspring loose with raw meat, buttermilk, flour and hot grease! But for the most part I tried to involve them in the process whenever I could because I wanted them to learn how to cook themselves. (No, I don’t mean cook themselves, silly; I mean cook for themselves.) Like everything else, there is no better teacher than experience. You can watch someone crack a thousand eggs, but until you try it yourself, you won’t be able to feel how much pressure it takes to break the shell without damaging the yolk. Breaking an egg takes practice. So does stirring and chopping and peeling and measuring and pouring and kneading.

It also takes patience from the teacher. A lot of patience. As anyone who has ever worked with them knows, little kids have small clumsy fingers, short attention spans and unpredictable curiosities. I found this out when showing my grandson, Aidan, how to make meatballs. He delighted in the feel of the cold, sticky meat mixture between his fingers, and although his spheres were less than uniform, at least they vaguely resembled meatballs. But what I didn’t expect was to catch him popping a raw one into his mouth, just to see what it tasted like! Still, I’d say the ordeal was totally worthwhile, even if it did involve a little tongue-scraping, because it exposed Aidan to the process of preparing a meal, and that kind of lesson is never wasted. So every time I am with him and his little sister, Avery, it is my self-appointed mission to cook with them. Sometimes we make cookies from scratch (the only kind worth eating!) and other times we roll weenies into "pigs in a blanket.” They’re both a little bit too young for cooking on the stove, but we’ll get there eventually. I can hardly wait. Together we’re going to flip pancakes, fricassee chickens, and flambé cherries.

It also takes patience from the teacher. A lot of patience. As anyone who has ever worked with them knows, little kids have small clumsy fingers, short attention spans and unpredictable curiosities. I found this out when showing my grandson, Aidan, how to make meatballs. He delighted in the feel of the cold, sticky meat mixture between his fingers, and although his spheres were less than uniform, at least they vaguely resembled meatballs. But what I didn’t expect was to catch him popping a raw one into his mouth, just to see what it tasted like! Still, I’d say the ordeal was totally worthwhile, even if it did involve a little tongue-scraping, because it exposed Aidan to the process of preparing a meal, and that kind of lesson is never wasted. So every time I am with him and his little sister, Avery, it is my self-appointed mission to cook with them. Sometimes we make cookies from scratch (the only kind worth eating!) and other times we roll weenies into "pigs in a blanket.” They’re both a little bit too young for cooking on the stove, but we’ll get there eventually. I can hardly wait. Together we’re going to flip pancakes, fricassee chickens, and flambé cherries.

And when we do, they’ll understand.

- Search for Cooking Class articles similar to "How I Learned to Cook in Just Fifty-Five Short Years.

- Search all articles similar to "How I Learned to Cook in Just Fifty-Five Short Years".

- List all Cooking Class articles.

Terms & Conditions | Contact | Login | This website designed by Shawn Olson